Welcome to Pox and the City. You can play our history game using the following link:

PLAY POX AND THE CITY: EDINBURGH

Please be patient as the game loads.

Pox and the City: Edinburgh

A Digital Role-Playing Game for the History of Medicine

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

Wednesday, June 5, 2013

Pox and the City, The Game

It has been an exhilarating ride, and now Pox and the City is finally a Game! Kudos to Elizabeth Goins, Lisa Hermsen and their team at RIT for turning a vision into reality.

It begins, as so much in Edinburgh does, in the Grassmarket, with Edinburgh Castle towering over the city. Young Dr. Robertson makes his way to the city. He has heard about Edward Jenner's smallpox vaccine, and is determined to use it to establish his own career.

His first decision is whether to play the game as a Philanthropic doctor -- that is, someone who became a doctor primarily to help humanity -- or as an entrepreneurial one, primarily interested in building his career.

Of course, the two are not mutually exclusive! If he's philanthropic, but gives away all his money and time, he won't be able to afford to stay in practice. And if he only cares about earning money, he won't find many patients willing to trust him with their lives and those of their children.

Having made his choice, Dr. Robertson finds himself in his office. This is a text-adventure game, and the journal in the lower right keeps track of his quests. His first quest is to read an important letter from Edward Jenner himself! But in order to find it, he first must clean up his office.

First challenge: how did people get rid of papers in 1802, before there were waste-paper baskets?

The player can look around the office to find additional information, like Jenner's 1798 text on vaccination:

It begins, as so much in Edinburgh does, in the Grassmarket, with Edinburgh Castle towering over the city. Young Dr. Robertson makes his way to the city. He has heard about Edward Jenner's smallpox vaccine, and is determined to use it to establish his own career.

His first decision is whether to play the game as a Philanthropic doctor -- that is, someone who became a doctor primarily to help humanity -- or as an entrepreneurial one, primarily interested in building his career.

Of course, the two are not mutually exclusive! If he's philanthropic, but gives away all his money and time, he won't be able to afford to stay in practice. And if he only cares about earning money, he won't find many patients willing to trust him with their lives and those of their children.

Having made his choice, Dr. Robertson finds himself in his office. This is a text-adventure game, and the journal in the lower right keeps track of his quests. His first quest is to read an important letter from Edward Jenner himself! But in order to find it, he first must clean up his office.

First challenge: how did people get rid of papers in 1802, before there were waste-paper baskets?

The player can look around the office to find additional information, like Jenner's 1798 text on vaccination:

He/she can also use the journal to find out more about Edinburgh locations important to the game.

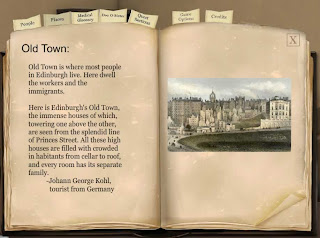

The Old Town is for the "lower orders": shopkeepers, artisans, and the laboring poor.

The New Town is for the people of rank and fortune.

But most people don't play the game to read: instead, they want to click on things and See What Happens Next.

Dr. Robertson can use the map to move around the city to meet patients and patrons.

He can build his practice with New Town families...

But most people don't play the game to read: instead, they want to click on things and See What Happens Next.

Dr. Robertson can use the map to move around the city to meet patients and patrons.

He can build his practice with New Town families...

who will invite him to elegant dinner parties:

And with their counterparts in the Old Town...

who will be less formal, but equally hospitable.

He will have to make choices: when to invest in smallpox vaccine, and how to persuade a patient to let him use it. He will have to figure out how to treat a range of diseases using only early 19th century treatments.

And what to do when beset by a host of challenges: a smallpox outbreak in the New Town, obstructionist physicians who refuse him access to medical records, and a missing cadaver that could -- if not found quickly -- destroy all his hopes of saving the world from the scourge of smallpox.

Not to mention, how to win at Speculation:

For an early account of our playtesting, go to the History of Vaccines blog from our project partner, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

Tuesday, March 5, 2013

The Making of Virtual Edinburgh: Medical Edinburgh on Jokaydiagrid

Classical Edinburgh took years to build, but with the aid of our Virtual World guru Desmond Shang, Medical Edinburgh on Jokaydiagrid was up and running in a matter of months.

It was an amazing experience for Euphemia Mason, lead avatar for the Pox and the City team, as she met with Des on what looked like a flat, empty lot, and watched it grow into a real city -- for a given definition of "real", that is. "I've put your map on the ground," Des said, and Euphemia went and stood on top of it, feeling exactly like Dorothy at the start of the yellow bridge road. The difference is, she got to describe the road, the buildings, the crescents, and the geography.

"This is the West Port," she said, a jumble of old houses as the edge of the social and economic world. And lo, the West Port was created, on the west side of the town heading towards the Glasgow Road, the long-distance route stretching across Scotland. By the 1820s, so many Irish immigrants had settled in the West Port and Grassmarket that the districts were known as Little Ireland.

"This is the West Port," she said, a jumble of old houses as the edge of the social and economic world. And lo, the West Port was created, on the west side of the town heading towards the Glasgow Road, the long-distance route stretching across Scotland. By the 1820s, so many Irish immigrants had settled in the West Port and Grassmarket that the districts were known as Little Ireland.

There's the Apothecary's and Milliner's...

The Tannery, which adds its distinctive smell to the surrounding area, and one of the many Edinburgh churches:

"And now we need to go UP to the High Street," Euphemia said. She explained that the road was very steep, narrow, and crooked, and Desmond, in turn, explained that was all very well for real-world builders, who could use stone and mortar and count on people not trying to walk through walls. Inworld, in Jokaydiagrid, if the roads got too steep, or narrow, or winding, they would block the avatars. Unable to climb, they would keep bumping into the road, and might even get stuck, locked for what seemed like forever in a virtual close or wynd.

So Euphemia settled on a nice, even incline, leading -- as all upward-tending roads in Edinburgh do lead, to the Castle at the top of the High Street.

Unfortunately we can't go in it, at least for now, but Euphemia can turn around and walk down the High Street toward St. Giles and Parliament Close...

One of the advantages Euphemia has over, well, the rest of us is that she can explore the famous crown of St. Giles from above as well as below. If mere mortals want to try for an almost-avatar's-eye view of St. Giles Cathedral, the best place for it is the Manuscript Room at the National Library of Scotland.

Surgeon's Hall, complete with skeleton and essential references to Burke and Hare...

and, a personal favorite, the library of the Royal Medical Society:

On to the New Town. Desmond carefully crafted geographical features along the way: South Bridge with its view of the Cowgate, and North Bridge leading to St. Andrew's Square. The New Town of Medical Edinburgh has been deliberately kept airy, light, and Georgian, to make a contrast...

with the tall, crowded, medieval buildings of the Old Town. This is the view that Euphemia can see from Princes Street, as she stands in front of what would be, in modern Edinburgh, the McDonalds. Thankfully, there is no fast food in Medical Edinburgh.

Euphemia and Desmond opted for crescents, not squares -- they're just sooooo beautiful -- but anyone who has been to George and Queen Streets should have no difficulty recognizing where Euphemia is inworld:

Of course in real life, the College of Physicians has walls, but still, Euphemia thinks Desmond did an excellent job of capturing the feel of the original 18th century building -- with its many pillars -- and its elegant furnishings. Not to mention another Burke and Hare reference.

And so, as Euphemia flies high above her virtual world, she sees stretched out before her, her vision of Old Town Edinburgh, beautifully rendered:

And of the New Town:

Medical Edinburgh is available to anyone on Jokaydiagrid. Proper behavior is required, on pain of being subjected to 18th century medical treatment.

Many thanks from the Pox and the City team (and especially Euphemia) to Desmond Shang, http://secondlife.wikia.com/wiki/Desmond_Shang, and to Jokay at Jokaydiagrid, http://jokaydiagrid.net, for making Medical Edinburgh not only possible, but actual and virtual.

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

Edinburgh Interiors

How do you create a world?

Answer, if you are a member of the Pox and the City team:

Through hundreds of photos, reams of archives, and not nearly enough opportunities to sample the variety of Edinburgh restaurants.

And so in May 2012, Hannah Ueno, Laura Zucconi, and I went to Edinburgh on a Six-Day Mission: To boldly explore the streets, wynds, closes, interiors, and archives of the city, so we can create the virtual world of medical Edinburgh. We'll have more on the process in later blogs, but for now, I'll concentrate on Edinburgh interiors, as a small way to say "thank you" to all the hospitable folks who let us wander purposefully throughout their historic buildings, cameras at the ready.

What better way to begin our exploration of early 19th century Edinburgh intellectual life than with a trip to Old College (University of Edinburgh) and the Playfair Library. Even though we did not have an appointment, the helpful staff at reception allowed us upstairs to visit what is surely among the most ornate settings for final exams in the the world.

Yes, we know it had not yet been constructed in 1802 -- we are historians, after all -- and that young Dr. Robertson would never have taken an exam with hundreds of others, as students do today. But he might well have sat with that many in his Anatomy and Surgery class, or carved graffiti on one of the desks, as we saw in our minute examination of the desks pictured on the right.

We decided we couldn't get enough of ornate libraries, and we were very fortunate that Ben Bennett, of the Scottish Council on Archives, provided us with a wondrous tour of General Register House, built by Scottish Enlightenment architect Robert Adam. Not only is it a classic example of an Edinburgh dome, but also its search rooms revealed any number of Pox and the city gems: blueprints of the New Jail on Calton Hill and Parliament House, letters from Scots lairds to their physicians about precautions to take against smallpox, and treatment if the precautions proved ineffectual. One minister called together all his parishioners -- or as many as would agree to attend -- and, with doctors and vaccines at the ready, carried out a kind of mass vaccination then and there, praying that the Lord "look favourably on the endeavours used to soften the effects of a loathsome disease to the children of this Parish and Neighbourhood."

the archive room...

and the most beautifully preserved 18th century interior in Edinburgh.

Many thanks as well to Marianne Smith, Librarian at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, for giving us a tour of the library and a glimpse of some of the most "special" of the collections, including an illuminated Book of Hours and a copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle.

And no trip to Medical Edinburgh could be complete without a visit to the Surgeons Hall museums! Photography isn't allowed inside the museum so I'll add one of my favorite images from their collection...

a preparation of the arteries of the foot. Gruesome, right?

Many thanks as well to Marianne Smith, Librarian at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, for giving us a tour of the library and a glimpse of some of the most "special" of the collections, including an illuminated Book of Hours and a copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle.

And no trip to Medical Edinburgh could be complete without a visit to the Surgeons Hall museums! Photography isn't allowed inside the museum so I'll add one of my favorite images from their collection...

a preparation of the arteries of the foot. Gruesome, right?

Stay tuned for more world-building as Pox and the City comes to a virtual environment near you...

Saturday, March 31, 2012

What’s in a Name? Or, Will Vaccination Turn Your Children into Cows?

When we think of vaccine, we think of injections. But when 18th century medical men thought of vaccine, they thought of cows. That’s because “vaccinae” is Latin for “of or pertaining to cows”, and the word entered the modern medical lexicon through the title of the famous 1798 work by Edward Jenner, “An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a Disease discovered in some of the Western Counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of the Cow-Pox.”

Many generations of admiring doctors and historians have noted this title without observing that Jenner was engaged in a bit of sleight of hand. The disease he described was, indeed known as the Cow Pox by those who had bothered to give it a name: the dairymaids and farmers who were most susceptible to it. The disease, as he noted, appears on the nipples of cows, and then is communicated to the dairymaids, and then “through the farm, until most of the cattle and domestics feel its unpleasant consequences”(1). It was Jenner, perhaps after consultation with his medical mentors, like John Hunter, who gave it the Latin name, starting with Variolae – the Latin medical term for smallpox -- and adding to it the designation Vaccinae – of or from cows. Borrowing from other 18th century medical nomenclature, which listed first the genus, then the species of the disease, the term variolae vaccinae indicated that the genus, or general class of disease, was variolae, pox, while the species was vaccinae of, by, or pertaining to cows. Thus Jenner’s name did double duty: it both conferred a learned Latin pedigree on a disease of “cattle and domestics” and used conventions of scientific nomenclature to establish the relationship between smallpox and cowpox.

This learned convention was incorporated into medical journals like the Edinburgh-based Annals of Medicine, which put in the 1800 index next to Cow-Pox, See Vaccine. And now that Jenner had brought it to their attention, practitioners began to “see vaccine” everywhere. It turned out that this disease of Cow Pox, and its attendant immunity from smallpox, had been part of rural folklore throughout southern England. Doctors located a similar set of beliefs in the West Country. The “country people of Ireland,” it turned out, were also “well acquainted with the disease”, and gave it the name of Shinah (2). The eminent medical professors at Edinburgh University were hard-pressed to explain why their benighted countrymen should have so unaccountably failed to develop so useful a folk-belief, and concluded that the cows of Scotland’s dairy districts, like Fife, simply did not get “the genuine vaccine disease”(3). Eventually, though, they were able to find a gentleman, “a most ingenious artist,” who could remember that his parents had owned a farm near the Scots town of Jedburgh, and that his mother, “who occasionally assisted the maids in the concerns of the dairy, never had smallpox, though frequently exposed to the disease” (4).

But as all these medical practitioners bustled around, making earnest inquiries as to vernacular names of what soon became known as the Vaccina disease, opposition was mounting. Matter from a cow used to treat humans! Introducing a “bestial humour into the human frame”! (5) Benjamin Moseley, one of the most vitriolic controversialists of his day, raged against the new practice, renaming it the Lues Bovilla (the bovine plague) a clear reference to Lues Venerea (the plague of venery) or syphilis. Moseley compared “Cow-Pock” to “Cow-Dung”, and gave graphic descriptions of supposed “nasty, filthy eruptions” he had seen in children who had been vaccinated(6); he claimed to have seen a whole series of new diseases, including Facies Bovilla, or Cow Pox Face, Scabies Bovilla, Cow Pox Itch or Mange, Tinea Bovilla, or Cow Pox Scaldhead. Most terrifying of all were his case histories, like the stories of poor Sarah Burley, “whose face was distorted, and began to resemble that of an Ox; and Edward Gee who was covered with sores, and afterwards with patches of Cow’s Hair,” as a result of inoculation by one of the “cow poxers”, as Moseley derisively termed them. Even more disgusting was the story of little William Ince, “vaccinated when four months old”, who broke out in all manner of sores and eruptions all over his body. They eventually dried up, but then there “appeared on his back and loins, patches of hair; not resembling his own hair, for that was of light colour, but brown; and of the same length, and quality, as that of a Cow.” The message was clear: vaccinate your child, and he will turn into a cow. And not even a healthy cow: as Moseley concluded, the child “remained in a miserable state, under various changes, until he was three years and a half old, when he languished and died.”(7)

Moseley’s rhetoric pushed pro-vaccine advocates on the defensive, so that they wound up writing panegyrics to the cleanliness and hygiene of Great Britain’s cows – “the most healthy of all animals” -- not unlike modern proponents of hormone-based drugs who, when criticized, point out that their chemicals come from yams (8)

And yet there was one area that both Jenner’s supporters and critics agreed on: the linguistic shift from “vaccinae” as an adjective referring to a cow, to “vaccinate” as a verb, meaning the inoculation with the disease entity known as a virus. Much later Louis Pasteur took up the verb and generalized it to apply to the medical procedure we know today. Now millions of people worldwide get their “vaccinations,” giving no thought to cows whatsoever.

References:

(1)Annals of Medicine, 1799,77.

(2)John Ring, A Treatise on the Cow Pox, London, 1801, I:28-30.

(3)Annals of Medicine, 1802, 446.

(4)Annals of Medicine, 1802, 321-4.

(5)Benjamin Moseley, Treatise on the Lues Bovilla, London, 1806, vi.

(6)Moseley, Treatise, 127.

Many generations of admiring doctors and historians have noted this title without observing that Jenner was engaged in a bit of sleight of hand. The disease he described was, indeed known as the Cow Pox by those who had bothered to give it a name: the dairymaids and farmers who were most susceptible to it. The disease, as he noted, appears on the nipples of cows, and then is communicated to the dairymaids, and then “through the farm, until most of the cattle and domestics feel its unpleasant consequences”(1). It was Jenner, perhaps after consultation with his medical mentors, like John Hunter, who gave it the Latin name, starting with Variolae – the Latin medical term for smallpox -- and adding to it the designation Vaccinae – of or from cows. Borrowing from other 18th century medical nomenclature, which listed first the genus, then the species of the disease, the term variolae vaccinae indicated that the genus, or general class of disease, was variolae, pox, while the species was vaccinae of, by, or pertaining to cows. Thus Jenner’s name did double duty: it both conferred a learned Latin pedigree on a disease of “cattle and domestics” and used conventions of scientific nomenclature to establish the relationship between smallpox and cowpox.

This learned convention was incorporated into medical journals like the Edinburgh-based Annals of Medicine, which put in the 1800 index next to Cow-Pox, See Vaccine. And now that Jenner had brought it to their attention, practitioners began to “see vaccine” everywhere. It turned out that this disease of Cow Pox, and its attendant immunity from smallpox, had been part of rural folklore throughout southern England. Doctors located a similar set of beliefs in the West Country. The “country people of Ireland,” it turned out, were also “well acquainted with the disease”, and gave it the name of Shinah (2). The eminent medical professors at Edinburgh University were hard-pressed to explain why their benighted countrymen should have so unaccountably failed to develop so useful a folk-belief, and concluded that the cows of Scotland’s dairy districts, like Fife, simply did not get “the genuine vaccine disease”(3). Eventually, though, they were able to find a gentleman, “a most ingenious artist,” who could remember that his parents had owned a farm near the Scots town of Jedburgh, and that his mother, “who occasionally assisted the maids in the concerns of the dairy, never had smallpox, though frequently exposed to the disease” (4).

But as all these medical practitioners bustled around, making earnest inquiries as to vernacular names of what soon became known as the Vaccina disease, opposition was mounting. Matter from a cow used to treat humans! Introducing a “bestial humour into the human frame”! (5) Benjamin Moseley, one of the most vitriolic controversialists of his day, raged against the new practice, renaming it the Lues Bovilla (the bovine plague) a clear reference to Lues Venerea (the plague of venery) or syphilis. Moseley compared “Cow-Pock” to “Cow-Dung”, and gave graphic descriptions of supposed “nasty, filthy eruptions” he had seen in children who had been vaccinated(6); he claimed to have seen a whole series of new diseases, including Facies Bovilla, or Cow Pox Face, Scabies Bovilla, Cow Pox Itch or Mange, Tinea Bovilla, or Cow Pox Scaldhead. Most terrifying of all were his case histories, like the stories of poor Sarah Burley, “whose face was distorted, and began to resemble that of an Ox; and Edward Gee who was covered with sores, and afterwards with patches of Cow’s Hair,” as a result of inoculation by one of the “cow poxers”, as Moseley derisively termed them. Even more disgusting was the story of little William Ince, “vaccinated when four months old”, who broke out in all manner of sores and eruptions all over his body. They eventually dried up, but then there “appeared on his back and loins, patches of hair; not resembling his own hair, for that was of light colour, but brown; and of the same length, and quality, as that of a Cow.” The message was clear: vaccinate your child, and he will turn into a cow. And not even a healthy cow: as Moseley concluded, the child “remained in a miserable state, under various changes, until he was three years and a half old, when he languished and died.”(7)

Moseley’s rhetoric pushed pro-vaccine advocates on the defensive, so that they wound up writing panegyrics to the cleanliness and hygiene of Great Britain’s cows – “the most healthy of all animals” -- not unlike modern proponents of hormone-based drugs who, when criticized, point out that their chemicals come from yams (8)

And yet there was one area that both Jenner’s supporters and critics agreed on: the linguistic shift from “vaccinae” as an adjective referring to a cow, to “vaccinate” as a verb, meaning the inoculation with the disease entity known as a virus. Much later Louis Pasteur took up the verb and generalized it to apply to the medical procedure we know today. Now millions of people worldwide get their “vaccinations,” giving no thought to cows whatsoever.

References:

(1)Annals of Medicine, 1799,77.

(2)John Ring, A Treatise on the Cow Pox, London, 1801, I:28-30.

(3)Annals of Medicine, 1802, 446.

(4)Annals of Medicine, 1802, 321-4.

(5)Benjamin Moseley, Treatise on the Lues Bovilla, London, 1806, vi.

(6)Moseley, Treatise, 127.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Dateline: Edinburgh, 1802

Now imagine that you live in Edinburgh in 1802. A young doctor in the city, Alexander Robertson, is trying to set up a vaccination dispensary, to protect people from the deadly smallpox virus while establish a paying medical practice.

A recent Irish immigrant, Charles McMahon, is working to set up a market stall on the Grassmarket -- but can he avoid contracting the deadly disease?

And through it all, the smallpox virus itself stalks the city, spreading contagion unless -- just unless -- the vaccine can shut it down.

If you can imagine this, then you can imagine playing the digital role-playing game Pox and the City, an RPG for the history of medicine. Funded with a Digital Start-Up Grant from the Office of Digital Humanities, a division of the National Endowment for the Humanities (http://www.neh.gov/odh/, the game is currently under construction, with beta-testing scheduled for spring 2013. It is a collaboration between Lisa Rosner and Laura Zucconi, historians of medicine at Stockton College, NJ, and the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Additional collaborators include Elizabeth Goins and Lisa Hermsen, Rochester Institute of Technology, graphic artist Hannah Ueno, and virtual world designer Desmond Shang.

We are currently working on the first episode of the game, in which Dr. Alexander Robertson must collect enough patients, and enough funding, to build a vaccine dispensary in Edinburgh's medical district. Will he be able to collect enough points to receive a charter from the Lord Provost and name his institution the Royal Vaccine Dispensary? Or will he be defeated by his nefarious rival? To find out, check this site for clues and updates as they emerge...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)